Peter Peterson and the Iron River Meteorite (and other U.P. stories)

Two wrongs may make a right, but two meteor_wrongs_ certainly don’t make a meteo_rite_.

And here’s why.

Well, first — let’s rewind.

To one day in 1889 when a six-year old boy named Peter Peterson (yes, this was actually his name) was helping his father clear rocks from a field near Iron River.

Things were proceeding as usual (I’m assuming) when little Peter noticed that one rock was much heavier than others of the same size. He showed the 3.13-pound whopper to his father who told him to toss it like the others.

But Peter, being a six-year old boy, kept it.

According to Von Del Chamberlain, a former MSU professor who recounts this story here, the rock was later identified as a meteorite, a fact which he later confirmed.

Look Up

When you look up at the night sky, you might be lucky enough to see a shooting star. Also known as a meteor, a shooting star is essentially a solid mass of space stuff shooting through our atmosphere in a fiery blaze of glory.

But the journey through the gaseous layers that surround Earth isn’t easy. Most meteors don’t survive the caustic journey, and break apart and are obliterated in the process. The ones that do make it and collide with our planet are called meteorites.

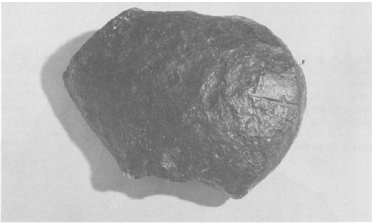

In the 1960s scientists finally got their hands on Peter Peterson’s meteorite, which was dubbed the “Iron River Meteorite,” and they discovered that, fittingly, it was made mostly of iron.

The Iron River Meteorite measures about 4.5 by 3 inches. Photo: Pulled from Von Del Chamberlain’s publication, “Meteorites of Michigan.”

And by using techniques that I won’t pretend that I even begin to understand, they estimated that it may have formed from a cosmic collision that occurred about 360 million years ago before it made its way to Earth.

To give you an idea of how long ago that was: 360 million years ago was just about when sharks made their way into the food chain, and when the plants, whose remains later created much of the coal we use today in our power plants, were alive and kickin’ it.

Or, if you’re like me and measure everything on the geologic time scale in comparison to the reign of the dinosaurs, that’s about 295 million years before T-rex and company were wiped out by, ironically, the effects of a large meteorite impact off Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

In short, the Iron River Meteorite really is, very old.

And confirmed meteorites are rare.

According to The Meteoritical Society, the Iron River Meteorite is currently the Upper Peninsula’s sole authentic meteorite, and one of only ten in the whole state (this excludes an impact crater labeled in the map below as “Calvin,” where I can only assume that the meteorite was destroyed on impact or never found).

Michigan is home to ten confirmed meteorites (nine plus the Calvin crater shown above). Only one, the Iron River Meteorite, has been found in the UP. Map created using The Meteoritical Society’s database and Google Earth

But, “doubtless, other real meteorites are present in Michigan,” writes Von.

They just haven’t been found yet.

Sorry, That’s a Meteor_wrong_

But, don’t worry. What we lack in meteorites, we makeup in meteorwrongs.

There are many cases of well intentioned citizens stumbling upon a curious-looking (or not-so-curious-looking) rock and incorrectly identifying it as a meteorite.

These stones with mistaken galactic identities are known as meteor_wongs_. (The Washington University in St. Louis also labels meteorwrongs as “leaverites” as in, “don’t bother picking it up, just leave it right there.”)

Von, who I should note is kind of a big deal in the meteorite field, describes two significant UP meteorwrong incidences.

In 1912, 23 years after the six-year old Peter P. stumbled upon a true meteorite, several fully grown men witnessed a meteorite shoot towards the horizon.

Later a metallic object was found in the area and someone enthusiastically bestowed it, you guessed it, a meteorite! But not only was it not a meteorite, it was a piece of manmade slag. (Slag is a by-product produced from the refinement or smelting of ore.)

Oops.

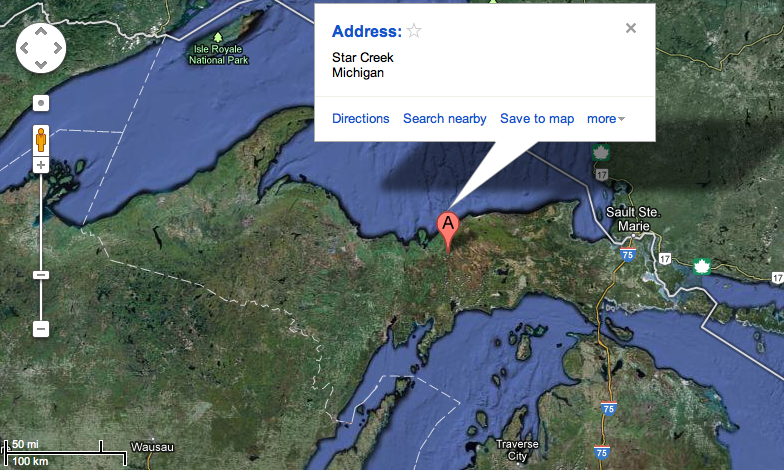

Despite the mistake, the legacy lives on and the stream that meanders its way nearby the “discovery” is still called Star Creek.

Star Creek still bears the name earned from a local meteorwrong “discovery.” Image: Google Maps.

But wait, there’s more.

Another meteor-whoops moment occurred near Grand Marais, notes Von.

In this case, a local resident stumbled upon a large glacial boulder after perhaps seeing a meteorite streak through the sky (no one is sure). Putting two and two together, the resident did not come up with four, but came up with a meteorite.

Author’s opening point; two meteorwrongs don’t make a meteorite, explained.

And there’s a lesson to be learned here.

“Experiences like this serve to emphasize the need for much care in reporting and interpreting dramatic but unfamiliar events,” writes Von.

But it seems that many have not heeded this advice.

You can enjoy the multitude of rocks that someone, somewhere, thought was a meteorite in this Meteorwrong Gallery from the Washington University in St. Louis. (I especially like number 3, which I swear I skipped across the surface of a lake the other day.)

UP Stargazing

Given the UP’s northern latitude and lack of light pollution, I’m thinking that UP stargazing has got to be some of the best in the Eastern United States.

A quick internet search will reveal extraordinarily beautiful images and videos like this one of the northern lights (also called the aurora borealis):

I admit that I haven’t gotten the chance to UP stargaze myself, but if you have please write in to UPSCo with your stories, experiences, and photos (even meteowrongs are welcome!) and we’ll share them in a UP dark sky roundup.

After all, Peter Peterson can’t be the only six-year old in the UP that’s pocketed a meteorite, right?

For More Awesomeness:

- For more information about Von Del Chamberlain

- Feel like a smarty-pants and read Von’s scientific article about the Iron River Meteorite

- Von’s publication Meteorites of Michigan

- Find great places to stargaze at the International Dark Sky Association

- To create your own star chart and, oh so much more, visit Sky and Telescope

- For alerts about the northern lights check out spaceweather.com